Covid-19 coronavirus: how the APAC courts and arbitral institutions have adapted to the challenge

Related people

Jane Jiang

Partner

Shanghai

Mark van Brakel

Partner

Perth

Fai Hung Cheung

Partner

Hong Kong

Matthew Hodgson

Partner

London

Sheila Ahuja

Partner

Singapore

Henry (Hyun Jik) Sohn

Partner

Seoul

Tina LeDinh

Managing Partner, Vietnam

Ho Chi Minh City

Daniel Ginting

Managing Partner, Ginting & Reksodiputro in association with Allen & Overy

Jakarta

Joshua Htet

Senior Associate

London

Headlines in this article

Related news and insights

Blog Post: 04 November 2022

Publications: 17 October 2022

Publications: 15 September 2022

The Supreme Court of Thailand issues judgement endorsing the use of SIAC Expedited Procedure

Publications: 27 May 2021

Commercially essential patents recognised as essential facility in China

As Covid-19 coronavirus continues to spread across the globe, the various forums for dispute resolution worldwide find themselves presented with novel challenges, in particular relating to issues around physical attendance at hearings. While much of the dispute resolution process is document based, up until this point, hearings have usually involved the parties, experts, witnesses and adjudicators gathering in person.

Having been forced to consider this issue slightly sooner than other parts of the world, the ways in which law courts and arbitration communities in Asia Pacific have coped and adapted to this issue may be instructive for other jurisdictions.

Responses by the APAC courts

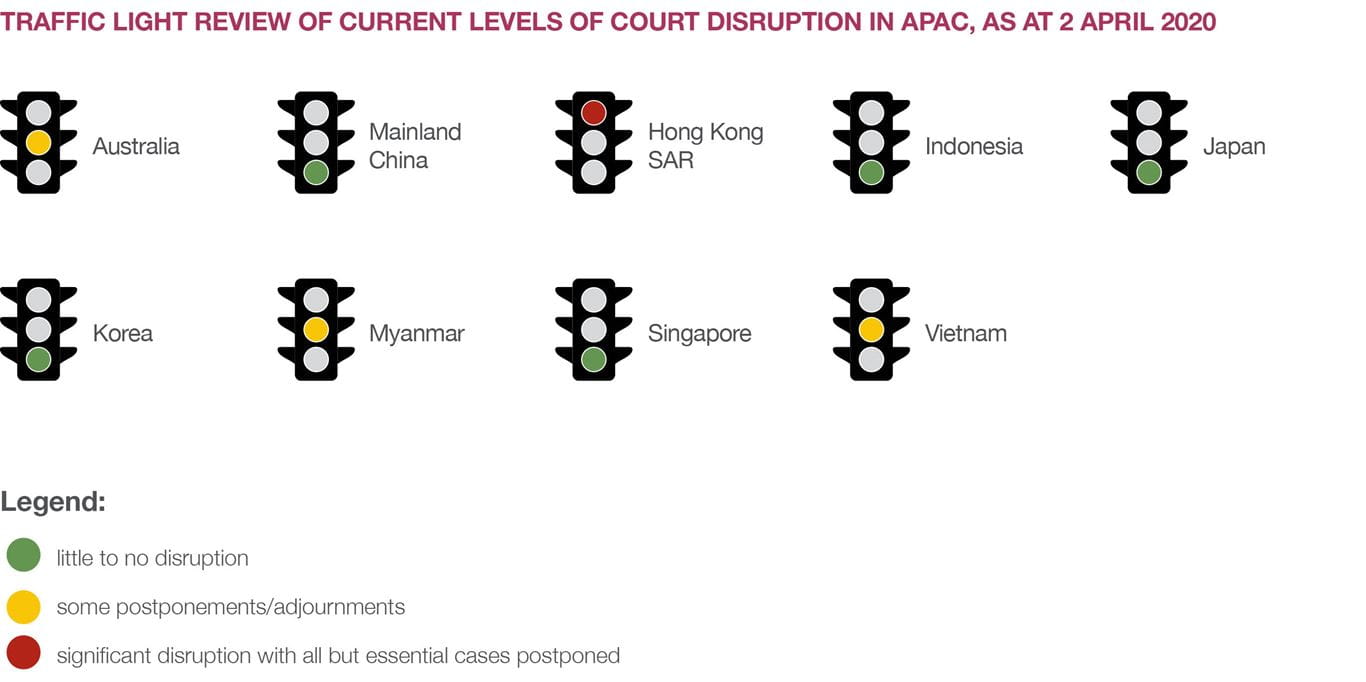

In a simple survey of eight APAC jurisdictions conducted by A&O, the majority of court systems appear to be holding up well so far. Speaking to our colleagues in Australia, mainland China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Singapore and Vietnam, with the exception of Hong Kong, all report that courts are now open with only mild delays or very minimal disruption. Some of them, like Korea and mainland China, substantially reduced operations for an initial period of a month or so but then returned to normal operation. Many, including mainland China and Australia, have, to the extent the rules permit, relied on technology and made attempts to be flexible.

However, as the Chief Justice of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal pointed out in a recent statement, the challenge is to ensure that such flexibility, including considering expanding the scope of hearings via telephone and videoconferencing, is “not only... logistically feasible but also legal in terms of being permitted by applicable court rules and procedures”. In his recent ruling allowing the use of telephone for a directions hearing (Cyberworks Audio Video Technology Ltd v Mei Ah (HK) Co Ltd), the Hon. Mr Justice Coleman adopted a pragmatic approach to the interpretation of the rules and procedures, but his reasoning demonstrated the hurdles faced by the judiciary and parties. A recent decision by the Western Australian Court of Appeal (JKC Australia LNG Pty Ltd v CH2M Hill Companies Ltd [2020]WASCA 38) ruled in favour of an appeal hearing proceeding by telephone and provides helpful guidance on how courts can provide “necessary and proportionate alteration to the normal practice and procedure of the court consistent with the due administration of justice”. However, it is noted that the decision is confined to cases where the hearing is on discrete questions of law with agreed facts and documents. A real challenge lies ahead for the conduct of trials in the courts if the current restrictions on personal attendance continue for an extended period of time.

In Hong Kong, the courts closely follow the government’s public health policy and the courts have applied a General Adjournment Period (GAP) since 29 January 2020, restricting services and adjourning all proceedings, other than certain urgent and essential business. The courts have gradually resumed proceedings in batches since early March, but with the latest increase in the number of confirmed infections, the GAP has now been extended for three weeks to 13 April. On 2 April 2020, the Hong Kong Judiciary issued a Guidance Note setting out the practice for remote hearings in civil cases in the Court of First Instance and Court of Appeal of the High Court during the GAP. Phase 1 entails using the courts’ existing videoconferencing facilities, but the note envisages the possible use of other technology in the future, provided it is feasible and secure. For the time being, the question of whether or not to have a remote hearing is for the court to initiate; parties cannot bring an application seeking one.

In mainland China, the courts have made good use of a recently introduced intelligent court application system, allowing parties to file documentation using an app, using biometrics for identification purposes. Though far from being commonplace, hearings via video-conference have also been tested and the possibility of using artificial intelligence to assist rulings has even been raised. The Chinese courts led the way in the use of technology in law courts even before the outbreak of the virus, and recent events have accelerated adoption. And thanks to the abating number of virus cases, China’s courts are largely back in business.

Litigation versus Arbitration

With courts at risk of closure and hearings being delayed or postponed across the region, there is an argument that, as a method of dispute resolution, international arbitration is better positioned to adapt to the sort of disruption being seen than litigation. One of the main advantages of international arbitration is its flexibility – the parties are able to agree on the timetable and ground rules by which the dispute will be resolved and are not bound by rules of civil procedure to the same degree as the courts are. Arbitral institutions are also better placed to make swift adjustments to their rules as required, given that they are not state institutions.

Most of the rules in place at the key arbitral institutions around the world grant the tribunal a broad discretion to decide the form of the hearing unless otherwise agreed by the parties, though only the rules of the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) (2014 edition) expressly contemplate a hearing by videoconference or telephone. In contrast, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) Rules (all editions) provide that the tribunal must meet ‘in person’ if any of the parties requests it do so, which may tie the hands of the tribunal when deciding on the possibility of a virtual hearing.

For the giving of testimony by witnesses, flexibility is provided by all institutions’ rules, again with the exception of the ICC, granting tribunals the discretion to unilaterally decide the form in which it is heard.

In practice, most case management hearings and many other procedural hearings in international arbitrations are already conducted by telephone. However, despite the discretion and flexibility of the relevant rules, it has been rare for a full-blown hearing to take the form of telephone or videoconference. One of the respondents to our survey reported having recently worked on a hearing in an arbitration seated in Singapore under the UNCITRAL Rules 2013 in which videoconferencing was used to hear from witnesses in India. That required a significant amount of planning and coordination to ensure that it went smoothly on the day. For another four-week hearing seated in London, under the UNCITRAL Rules 1976, the parties decided to adjourn the hearing due to a lack of confidence in a multi-party videoconference, particularly in light of the need to use visuals and to refer to substantial documentation. Many advocates consider that the “impact” of a cross-examination may be significantly reduced if conducted by videoconference. However, with no certainty as to when the pandemic will pass, virtual hearing technology continuing to improve, and uptake progressing through the legal services industry, it is perhaps only a matter of time before all litigants, tribunals and institutions alike will be forced to consider ways to mitigate the downsides of using technology in this way.

Long term implications

Discussions about the increased use of videoconferencing in dispute resolution are not new, but it has gained limited traction to date. During Hong Kong’s Civil Justice Reform commenced in 2000, it was decided not to dispense with attendance at hearings due to a lack of interest from parties and the cost to the courts of investing in the required technology.

However, the intervening two decades have seen enormous technological developments and it may be that, as Justice Coleman pointed out in his recent ruling, “The Covid-19 crisis is actually an opportunity for the courts and parties to reassess how cases can best be managed. Whilst the ruling [to allow the telephonic hearing] is born of the current circumstances, and addresses those circumstances, there seems to me to be a strong argument for moving matters in a similar way beyond the end of the crisis.”

While the current crisis will, we hope, be shortlived, Covid-19 has the potential to drive adaptations to arbitral and litigation proceedings that could have a much more lasting impact.