Real-world disputes in the virtual world

Contents

The laws that govern the metaverse are grounded in those of Planet Earth. Private civil laws relating to contract, tort, IP and data privacy all bite, as do criminal and regulatory laws. Where the difference lies is in their application to a new environment.

“Good morning to everyone in Santa Marta, Magdalena, Colombia, this 15th day of February 2023.” So began Colombia’s first hearing in a metaverse. When the clerk said the equivalent of “Court rise!” all the avatars (and presumably the humans) duly rose.

Many of us, whether in a professional or leisure capacity, spend vast amounts of time online. The global pandemic amplified this further. But we are still only on the cusp of interacting via immersive virtual or augmented reality on a regular basis, as Colombia’s experiment prefaces. That will inevitably change. When it does, it will bring with it legal and regulatory challenges.

With AI occupying most of the headlines about technology, it is easy to forget how much is being invested in virtual reality or spatial computing. Meta allocated more than USD18bn to research and development in the first two quarters of 2023. Apple has recently showcased Vision Pro, its virtual reality headset. And Microsoft, subject to regulatory approvals, is seeking to acquire Activision Blizzard, the immersive entertainment house behind games such as Call of Duty and Candy Crush, for nearly USD70bn.

In July, the European Commission adopted a new strategy on “Web 4.0 and virtual worlds” because of the potential of the technology to revolutionise the daily lives of people, as well as create opportunities for business.

McKinsey calculates that “the metaverse” has the potential to generate USD5 trillion in value by 2030. The European Commission estimates that the “global virtual worlds market size” may grow to more than EUR800bn over the same period.

However, it is difficult definitively to work out the current size of the metaverse because of a lack of independently verifiable data and different approaches as to what it constitutes. Microsoft, for example, has said: “When we think about our vision for what a metaverse can be, we believe there won't be a single centralised metaverse, and there shouldn't be.”

It is also clear that a sizeable chunk of the value currently lies in gaming. Platform providers, analysts and other commercial players hope that the generation that has grown up playing in virtual worlds will want to work in them too.

More broadly, the prediction is that there will be a rise in participation and investment by consumers and ultimately businesses, and that metaverses or at least a far greater degree of virtual interactivity will become a major economic and social force, capable of emulating various aspects of our daily personal, professional and social lives.

To date, the activity has been mostly in the consumer sector but there are business opportunities; from the greater use of 3D modelling and simulations in research and development, to the obvious benefits in training individuals, be they mechanics or surgeons, through to the creation of virtual trading floors.

With increased personal and commercial use comes the increasing risk of disputes. How these disputes may pan out, and what rights and remedies prevail, matters to consumers and businesses alike.

Disputes risks that should be considered

Metaverses can range from the simple to the all-embracing. We have identified the principal areas that may give rise to disputes risks:

Ownership

The question of ownership in the context of the metaverse can be applied to a metaverse itself, the digital “assets” within it, rights to personal data, and intellectual property rights. All have the potential to give rise to disputes about who owns what and the terms on which those things can be used.

Who owns a metaverse?

In centralised metaverses, there is a high degree of certainty around ownership; the companies that create them will own them and regulate the nature of, degree to which, and how users interact with each other and the metaverse itself. There may be some debate around the edges, for example, about what is part of the environment and what is an “asset” within the environment.

Decentralised metaverses will typically not have any central authority control. They are – at least, in theory – owned and governed by a user community via decentralised autonomous organisations. These governance structures enable all users to decide on the rules and policies of a metaverse. The position on ownership is therefore more fluid and open to a risk of complex disputes since users may require the cooperation of pseudonymous others to assert joint ownership and may not know the identities of those who they claim are impinging on their property rights.

Digital assets in the metaverse

Digital assets within a metaverse may take many forms; they may be virtual representations of things we encounter in the physical world, or concepts that only exist in a metaverse. People may buy virtual land on which they may build their dream virtual house, a business may open a virtual shop in which it sells virtual wearables, people may create virtual art to be sold or exhibited in virtual art galleries, or copies of artworks that exist in the physical world. These digital assets may have a value.

In centralised metaverses the terms of engagement will be primarily contractual. In essence, this means that who owns that value and how it is to be transferred will all depend on the terms and conditions.

For decentralised metaverses the analysis is potentially more complex, including the extent to which personal property rights may vest in these digital assets and to which people may assert competing interests.

The use of blockchain technology and, in particular, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), allows a representation of the digital asset to be unique, and for “ownership” to be transferred by transfer of the NFT. So far, in relation to digital assets generally, the courts in England and the U.S. have proved to be adept at accommodating these novel asset types and their claimed pseudonymity, but a body of case law has yet to be built up, meaning there are greater disputes risks than for classic personal property rights.

Personal data

The laws on the use of personal data (for example, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation) apply to a metaverse just as to any other online interaction.

In a metaverse, users enjoy an immersive experience using technologies that allow them to interact with others and the environment as if they really are present in that alternative reality. The processing of personal data is essential to this experience. What is potentially different to other online experiences is that unprecedented amounts and types of data may be collected about users that may well reveal their inner thoughts.

One academic has coined the term “biometric pyschography” to describe the use of “behavioural and anatomical information (eg, pupil dilation) to measure a person’s reaction to stimuli over time [which] can reveal both a person’s physical, mental, and emotional state, and the stimuli that caused him or her to enter that state.”

In practice, data collected about an individual may include information like eye tracking and pupil response, head nodding, facial expressions, bodily movements, galvanic skin responses, and even brain activity. As users are logged into the digital world for sustained periods, their personal data will also be collected on an ongoing basis.

The personal data collected in a metaverse may be used for many reasons, including:

- Improving the user’s experience as avatars: for example, a wearable magnetic sensor system worn by users may track their body poses to mimic the experience of a “soldier” avatar wielding a sword and wearing armour.

- Personalising avatars: “avatar personalisation engines” may be used to personalise 3D avatars based on a user’s photo, including using “skin replicators” that may simulate a user down to every pore, every strand of hair, every micromovement.

- Giving commands: Apple’s Vision Pro can be controlled with your eyes, hands and voice.

- Targeted advertising: information such as eye-tracking will make it much easier to measure a user’s attention and engagement with content, including advertisements. For example, avatars frequently glancing at a virtual café or peering inside a virtual bakery window may prompt the appearance of targeted restaurant or food advertisements.

This all needs to be analysed against the patchwork of regional and national data privacy laws that apply in different countries, and which place different obligations on entities depending on how they collect, process and use data.

Areas that have the potential for increased disputes risks include: the treatment of “biometric psychography”; understanding who is in control of, and so can be held to account for any misuse of, personal data in a decentralised metaverse; ensuring adherence to data protection principles when a user may not meaningfully appreciate the significance of the data being collected about them; and, in the case of decentralised metaverses, ascertaining who is the data controller or equivalent.

Intellectual property

A metaverse presents both a new market for owners of intellectual property and a place where the rights of those owners may be infringed in new ways.

Taking trade marks as one example, they are applied for in relation to particular goods and services. The system of classification for these goods and services was conceived very much with the physical world in mind, but it has been adapted over the years (the latest update expressly provides for NFTs). Additionally, trade marks are national rights and metaverses are not so confined. Brand owners who have not already done so may therefore want to update their trade mark portfolios in terms of goods, services and territories covered.

We are already seeing trade mark infringement cases being brought in relation to uses by way of NFTs. Globally recognised, long-standing brand owners are jealously protecting their property.

In 2022, Nike filed a complaint against the resale marketplace StockX, in the Southern District of New York, claiming that it is selling NFTs that display Nike’s shoe designs without Nike’s permission. StockX’s defence is that the NFTs are not digital art but rather they represent an entitlement to physical shoes. That dispute is ongoing.

In February 2023, a jury, also in the Southern District of New York, found in favour of luxury brand Hermès in its dispute over the digital representation of its famed Birkin bag, bearing the name “MetaBirkins,” being offered for sale on various NFT market places. Even NFT natives are asserting their rights. In April 2023, Yuga Labs (of Bored Apes Yacht Club renown) obtained summary judgment against Ryder Ripps, a self-proclaimed “conceptual artist,” for trade mark infringement from the Central District of California.

Content moderation

Social media companies already face significant challenges in protecting users from online harms. From a technical and practical perspective, the solutions are difficult to come by. Even though AI may be used, that will require human training, and any system will have an element of human review.

The EU’s Digital Services Act, which passed into law last year, and the UK’s Online Safety Act, has just become law having been four years in the making, are examples of the responses from legislatures, driven by public concerns. In the U.S. it is more a question of following the case law on, and slim chances for legislative change to, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and the Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

The challenges of moderation only increase multi-fold when you are concerned with an immersive virtual experience in which content is being generated in real time. The variables are greater and the user’s experience of any harm likely to be more palpable.

It remains to be seen which legal systems will have struck the right balance between reducing online harms and preserving existing freedoms, and the exposure to disputes that flow from that approach.

Emotional distress caused by an interaction in a metaverse

Whether you can be liable for causing pure emotional distress in the absence of physical injury, and if so how any damages are calculated, will vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

The starting point is likely to be who owes a duty of care. This could be the headset manufacturer, the provider of the metaverse, or any person that created the peril (U.S.) or is found to have assumed responsibility (England). Generally, manufacturers owe a duty of care to ensure their products are safe.

It would then be necessary to show breach of that duty to the extent it had not been excluded or the possibility of it forewarned.

In relation to any distress suffered, at least in common law jurisdictions, whether a person can claim for witnessing, for example, physical harm suffered by others when they suffer no physical harm (or threat of harm) themselves is likely to depend on questions of proximity and reasonable foreseeability, as well as being able to demonstrate actual psychiatric harm.

The facts of cases such as these are extreme. In Australia parents were able to recover for the psychiatric injury caused by identifying their son’s blood-stained belongings and skeleton. Whereas in England, people watching or hearing about their friends or family being hurt or killed during the 1989 stampede and crush at Hillsborough football ground were not permitted to claim compensation, since to establish a claim for psychiatric illness resulting from shock it was necessary to show that the injury was reasonably foreseeable, and that the relationship between the claimant families and friends and the defendant police force was sufficiently proximate.

In the U.S., the viability of a claim will vary from state to state, but many states currently require that the victim be in the “zone of danger” – that is, unless the victim themselves was threatened with physical injury, there may be no claim for damages.

Whether the distinction between physical and psychiatric harm would continue to be drawn is open to debate. Our understanding of the medical causes, impact and treatment of psychiatric and psychological conditions has progressed considerably.

In addition, cultural attitudes in many jurisdictions are shifting so that mental illnesses are viewed in the same way as physical ones. Furthermore, widespread use of the technology and the potential increase in these types of issues may lead to a change in the law to allow for claims to be pursued that may currently be precluded.

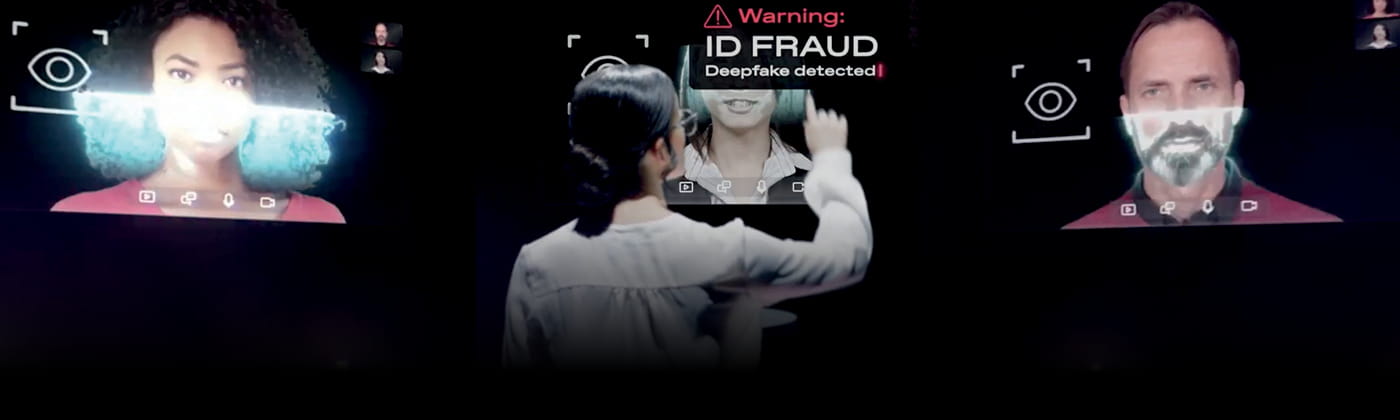

Identity theft

People in a metaverse are likely to want the ability to identify the person behind the avatar and to prevent anyone from masquerading as them.

In the Colombian metaverse hearing, ahead of the virtual proceedings beginning in earnest, each participant had to go through several steps to verify their identity including showing a video or photograph of the participant and ensuring that the avatars had as true a likeness to the real individual as possible.

The use of NFTs may offer a potential technical solution to matching avatars with the people behind them. They also allow for the possibility of moving from one metaverse to another while retaining a unique verifiable virtual identity.

The potential for fraud is readily apparent. The laws that may bite and lead to disputes are likely to be those that have always applied to such deception (eg, criminal fraud or its equivalent). Some jurisdictions, for example the U.S., have criminal offences aimed specifically at identity theft.

In others, like England, the mere acquiring of information that identifies an individual (like date of birth, name, home address, etc.) is not a criminal offence but likely a precursor to one. So, the fraudster can be prosecuted at the point the stolen information is used to obtain goods or services by deception. Either way, while the vehicle for the dishonesty may be novel the means of prosecuting it are unlikely to be. The challenges are more practical; how to locate the perpetrator, who may well be outside of the jurisdiction.

Disputes in the metaverse

Will we see a day when metaverse disputes will be resolved before a metaverse tribunal under a metaverse law? The answer to this intriguing question may be unclear today, but there are several factors that could help shed light on the feasibility of it happening.

Informal dispute resolution can and does work

Online businesses selling goods and services and those acting as marketplaces have long had alternative or informal dispute resolution mechanisms that have been highly effective for most disputes.

If there was a demand for an entirely intra-metaverse dispute resolution system, and one evolved that satisfied most users most of the time, it may well be effective in practice, even if the users could in theory still assert their strict legal rights.

English/EU courts do not accept non-country choice of law

Looking at that stricter position, EU and UK legislation on applicable law refers, throughout, to the law of a member state or the law of a country. Without reform, therefore, a choice of a “metaverse law” is unlikely to be enforceable by the English courts or the courts of an EU member state.

Perhaps the most likely outcome in a dispute where the parties have agreed to abide by a set of metaverse rules (even if they are described as a “law”) is that a court will see these rules as terms of the contract between the parties rather than a choice of law. The law of a country will be found to be the true governing law underpinning the parties’ relationship.

Arbitration potentially more flexible on choice of law

In arbitration, the position is probably more flexible on applicable law. Parties (especially governments or international organisations) do agree to have disputes resolved by international arbitration, choosing general principles of law, or public international law as a governing law, and these choices are upheld by tribunals.

Nevertheless, it is a considerable leap from asking a tribunal to apply general principles of law to asking it to ascertain and apply a given metaverse law.

Put simply, when it comes to governing law, parties should expect the law of a country to apply to their relationships within the metaverse for the foreseeable future.

The more immediate issue on governing law is likely to be identifying which national law applies in circumstances where none has been chosen by the parties.

Choice of forum

If a dispute arises, it may be perfectly possible to resolve it wholly within the platform on an informal basis according to the platform rules and without ever knowing the real identity of the parties. A decision rendered in this way will not have the legal effect of a court judgment or arbitration award.

It will not, for example, allow one party to enforce the outcome against the losing party’s assets in the real world. It could, however, be enforced directly against their assets in the virtual world, perhaps even automatically, in the case of a self-executing dispute resolution mechanism in a contract, through transfer of funds between digital wallets.

To bring any kind of civil litigation, a court will have to be persuaded that it is the appropriate forum. Moreover, the identity and location of the parties will need to be ascertained. In high value cases private investigators or business intelligence units may be deployed. In some instances, a court may allow the defendants to be described, for example, as “Persons Unknown” rather than named.

The consent of the parties is required if a dispute is to be resolved by arbitration, but there would be nothing to stop participants in the metaverse agreeing to arbitrate their disputes.

Whether that arbitration could be legally located in the metaverse itself is a more difficult question.

Commercial arbitration is anchored by having a legal seat in a real-world territory. The seat is important for a number of reasons. It will determine the curial law – the law in which the arbitration sits – so if arbitration is expressed to be London-seated, it will be governed by the UK Arbitration Act 1996 and the English courts will have supervisory jurisdiction over it. The seat of the arbitration is also relevant to the recognition and enforcement of any award and whether it can be enforced under the highly successful New York Convention that has over 170 states as signatories.

For the moment, this would seem to pose a serious challenge to having an arbitration seated wholly in the metaverse without reference to a physical territory or national legal system (although there is no reason why hearings could not take place in a metaverse).

However, arbitration may provide a route to resolving one potential issue. The UK Jurisdiction Taskforce, part of a UK government-backed initiative group promoting the use of English law and English courts, has proposed a set of Digital Dispute Resolution Rules and Guidance which suggests that disputes could be resolved by arbitration or expert determination with the parties being anonymous to each other but not to the tribunal or expert to whom a dispute is referred. These rules were designed with digital assets like crypto tokens in mind but they could be adapted for use more widely in a metaverse and potentially represent a neat hybrid solution to the challenge of anonymity.

Enforcement

When it comes to enforcement, the disputing parties may well be content to abide by any internal adjudication in a metaverse which could entail, for example, the transfer of a digital asset, or compensation in the form of that metaverse’s “currency”.

If the question is of more formal legal enforcement, there are two perspectives from which it can be analysed:

- Scenario 1: will a court or tribunal respect a “metaverse decision” and enforce it in the real world without re-examining the merits?

- Scenario 2: conversely, can a court or tribunal decision be enforced in a metaverse?

Scenario 1

The rules could state that a metaverse tribunal decision is contractually binding. This would allow a party to bring proceedings for breach of contract if the rules were not complied with.

However, a claim for breach of contract is not the same as having an enforceable court judgment or arbitral award. A party would first need to sue for breach of contract, and then if successful, that party would have a judgment or award.

Further, the issues already discussed – anonymity (and identifying who to enforce against), the lack of a legal seat (if the process is seen as arbitration), ascertaining what a “metaverse law” is – as well as possible concerns about whether the “metaverse decision” accords with public policy and due process, create uncertainties (though not necessarily all insurmountable ones) about enforcement.

Scenario 2

Courts and tribunals have always been able to order the parties before them to do things (eg, take all necessary steps to transfer x to y).

The English court, for one, has adopted an expansive approach to helping those who have been defrauded, or otherwise unlawfully deprived, of their digital assets. Even if a blockchain is effectively “immutable,” a court or tribunal can still order that an equal and opposite transaction is entered on the system or order restitution of the value.

There are, of course, limits to what a court or tribunal can and will order. It will not have jurisdiction over property that is legally situated in another country nor over people who are not before it and are in another country.

Rule of law in the virtual world

There is an instinctive tendency with any significant technological development to imagine that it somehow exists in a legal vacuum. It was a common refrain back in the early days of the world wide web that the usual rules could not apply.

In fact, in many instances, the old rules can be applied to new circumstances, albeit with some adaptation. This was largely the case for the web. Some technologies, like Bitcoin and AI, do raise some questions that are not immediately obvious from the existing legal regime. With metaverses, that is predominantly not the case. The laws that operate currently in virtual worlds are very much grounded in those of the real world. Private civil laws like contract, tort, intellectual property and data privacy all bite, as do criminal and regulatory laws.

Some jurisdictions are introducing legislation to address online harms, but largely the legal regime is the one we are used to, it is the application of that to a new environment that is different.

Living in the virtual world

The prospect of a future where we may lead parts of our lives in the metaverse may still seem to some to be closer to science fiction than a likely imminent evolution of what we do today in the physical world. But the potential power of virtual worlds to extend and affect human experience (in all its complicated entirety) is irrefutable.

Sooner or later, metaverses, like social media, are likely to become yet another digital communication channel that shapes and influences our personal and professional lives. And when that happens, managing the myriad future disputes risks that are likely to emerge will also become a day-to-day part of our lives.