Artificial intelligence in arbitration: evidentiary issues and prospects

Related people

Headlines in this article

Related news and insights

Publications: 04 April 2024

Deconstructing Crypto Episode 10: SBF, AI-Washing and Major Case Developments

Publications: 21 March 2024

Publications: 05 March 2024

Blog Post: 26 February 2024

Martin Magal, Alexander Calthrop and Katrina Limond of Allen & Overy examine how artificial intelligence will change the way in which parties gather, analyse, and present evidence in international arbitration – concluding that while the technology will not replace lawyers, practitioners who use AI may well replace those who do not.

The AI genie is out of the bottle.

Released in November 2022, ChatGPT, the AI chatbot, is the fastest growing consumer application in history.

Its latest iteration, GPT-4, has wowed (and terrified…) with its apparent displays of human competitive intelligence in a broad array of fields. It scored in the top 10% of a simulated bar exam, achieved a near perfect SAT science score, and obtained similar results across a wide range of professional and college admission exams.

At Allen & Overy, our lawyers are able to use a GPT-4 based platform called Harvey to automate and enhance various aspects of their work.

Ask Harvey to prepare a memo on privilege under English law, and it will prepare one within seconds (at a level of competence that will surprise many practitioners). Ask it to do so in the style of Donald Trump, or the author of 50 Shades of Grey, and you will be impressed (and amused) by the results.

This is a remarkable feat. As recently as October 2022, if you had received a coherent memo on a legal topic, this would have been proof of human involvement (if not quite human intelligence…). That assumption is now obsolete.

It is natural to wonder, how far will this go? What will AI models be able to do, and how will we humans fit in? These developments seem certain to have profound implications for our society; and it is naïve to assume that international arbitration will be immune.

Against that backdrop, we consider below how AI may transform the practice of international arbitration. We focus on evidence, and how AI may, in the imminent and conceivable future, change the way in which parties gather, analyse, and present evidence. (This is a synopsis of a chapter by the same authors to appear in the upcoming second edition of the GAR Guide to Evidence in International Arbitration.)

Our core hypothesis is that whilst AI will not replace lawyers, lawyers who use AI may well replace those who do not. But the road will not be without its speed bumps. Using AI comes with risks and users cannot blindly follow its outputs (as one sorry U.S. lawyer recently discovered).

AI’s use for evidence – a bright future?

Given AI’s emerging capabilities in analysing and manipulating language – at speed and at scale – it seems obvious that AI could have powerful potential applications for identifying, finding and analysing evidence.

Claim development

Consider, for instance, an AI tool that proactively reviewed your company’s contracts, emails and documents, and alerted you to evidence of claims and defences. Sound far-fetched? Maybe less than you think. Microsoft recently announced “Copilot”, which envisages integrating GPT-4 based AI across the full suite of Microsoft 365 products (e.g. Windows, Outlook, Teams, Word, Excel, etc.). Its promotional video offers an eye-opening glimpse into what knowledge work, including legal work, could look like in the future. Time will tell if Copilot it ultimately lives up to the hype, including whether it could be used for legal work – but it certainly raises interesting possibilities. Multiple legal tech companies claim to have tools enabling contractual compliance review or identifying, organising or summarising evidence.

Pleadings

AI may also have the potential to assist lawyers with reviewing submissions. AI has already demonstrated promising capabilities in summarising content. It seems plausible then, that before reading thousands of pages of legal submissions, exhibits, witness statements, expert reports, and so on, lawyers could first upload everything to an “AI Assistant” and ask for:

- a summary of all the key points, both for the submission as a whole and for each individual document.

- initial ideas for counter arguments and evidence based on the documents your AI has access to (e.g. on a data room and in the public domain).

- any relevant trends or tendencies you should be aware of in recent case law or for your tribunal (e.g. based on their publications or publicly available awards concerning their attitude towards certain issues), so as to inform what evidence and arguments you should focus on.

Now of course, any lawyer worth their salt would ultimately need to read, and re-read, and then re-re-read, the submissions. They could not rely on the AI. But such a preliminary review would undoubtedly be useful. Not only would it speed up understanding, but it would help identify evidence and ideas for your response that may otherwise have been missed. Perhaps, the AI could even have the first go at the reply submission.

Disclosure phase

AI’s potential to transform the disclosure phase also seems evident. Rather than running search terms (which tend to generate many false positives), perhaps the underlying document requests could be run as prompts in the AI model, which would then review all the documents and identify those which may be responsive. Advanced AI-driven search technology is already being rolled out for litigation purposes. The potential cost and time savings are obvious.

Witness statements

From a technological perspective, there seems no reason why voice recognition AI could not listen to fact witness interviews and – with the help of a generative text AI – prepare first drafts of statements. Could this help prevent distortion of witness memory? Or would it give rise to criticism that the statement is not in the witness’s own words, but those of an AI? And is that preferable than lawyers doing so, as is common in many jurisdictions?

Merits hearing

AI’s possible use during hearings is especially intriguing. Suppose AI listened to the hearing, and reviewed the transcript in real time, whilst simultaneously looking for counter arguments and evidence – both on the record and in the public domain – to what opposing counsel, witnesses or experts were saying. Such a tool would be powerful, but also dangerous. The risk of missing a “hallucination” (a confident but inaccurate AI response) would be especially acute in the heat of battle. Counsel would need to be especially careful not to mislead the tribunal.

The risks of using AI

The above tools would clearly offer productivity and performance gains. There are, however, important limitations and risks which cannot be ignored.

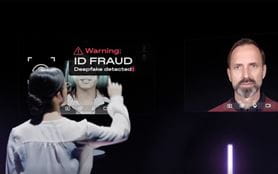

Hallucinations

It is well documented that AI will sometimes confidently assert incorrect answers. These “hallucinations” can even come with fabricated footnotes and sources, including entirely made-up case names. As lawyers, accuracy and credibility are paramount, so this is clearly a major cause for concern.

AI developers are working on ways to reduce hallucinations. But as trusted counsel, with fiduciary duties to our clients and a duty not to mislead the tribunal, it is clear that we (as well as arbitrators) should never be “handing over the keys”. AI outputs should be treated as first drafts from an inexperienced junior, but one who prefers to concoct an answer rather than confess ignorance. As such, learning how to effectively prompt AI, and to verify its outputs, will become an increasingly key skill.

Some “hallucinations” will be easily verifiable (such as a fake case names); others may be more subtle. For instance, data can contain cultural biases that affect an AI’s output. At our firm, we have encountered situations where AI trained on U.S. data has misinterpreted UK documents. The AI labelled as “positive” responses that UK readers would recognise as being passive aggressive. In a multicultural field such as international arbitration, being aware of such biases in AI models will be particularly important.

Regulatory compliance

Where technology advances, regulation is sure to follow. Indeed, legislators in many jurisdictions are proposing AI-specific regulation. It is not a given that the AI technology described above will always remain compliant with new and differing regulations across all relevant jurisdictions. For instance, In June the European Parliament voted in favour of regulation that will form the basis of Europe’s Artificial Intelligence Act. If adopted in its current form, many popular AI tools would – as things now stand – be rendered non-compliant.

The onus will be on arbitration practitioners to ensure any use of AI complies with applicable regulations. This may extend beyond their home jurisdiction, to include the laws of the seat and place of enforcement. Parties may attempt to resist enforcement of an award on the grounds that the other side’s use of AI was illegal under one of the applicable laws to the arbitration, or the use of AI was procedurally unfair as one party had access to AI tools while the other party did not, due to different AI rules in their respective jurisdictions.

Arbitral rules and institutions

Currently, arbitration rules and institutions provide either little or no guidance with respect to AI. The major arbitration rules do not currently address AI, either as a means to aid disclosure or more generally. The Silicon Valley Arbitration & Mediation Center recently published draft guidelines concerning AI’s use in arbitration, which are open for comment until 15 December 2023 for members of the public and 15 February 2024 for institutions. It remains to be seen how those guidelines will evolve following the public consultation period, and whether they end up being influential within the international arbitration community. A major focus of the guidelines is: (i) promoting understanding of AI’s limitations and risks, (ii) safeguarding confidentiality, (iii) ensuring competent and diligent use of AI, including appropriate disclosure of its use, and (iv) ensuring arbitrators do not delegate their decision-making responsibilities.

Confidentiality

AI requires large amounts of data to function well. Indeed, the uses of AI considered above, presuppose that all documents in the arbitration have been uploaded onto the relevant AI platform. For many clients, this would (understandably) raise alarm bells to the tune of data privacy and confidentiality.

A recent example shows the reasonableness of these concerns. A coder at Samsung, in search of a fix for a bug, uploaded lines of confidential code to ChatGPT on two separate occasions. Since ChatGPT takes user inputs to train its model, this code was subsequently reproduced in response to users from other organisations.

Importantly, not all AIs operate this way. Some AI platforms, such as Harvey, use closed systems whereby any information submitted by a user is secured, and cannot be reproduced in future responses. Lawyers who make use of AI will need to be certain that the AIs they use maintain the confidentiality of client data.

Conclusions

The world seems set to embark on a new AI-driven era. The implications for society will be profound, and lawyers cannot afford to be blind to these developments. Not only do they offer the possibility of significant productivity and performance gains, but those who ignore AI may find themselves left behind.

Yet, AI’s adoption in international arbitration will not be without its challenges, including ensuring the reliability, security, and ethical standards of the technology, and gaining the trust and acceptance of clients.

AI in this context is not a threat to the legal profession, but rather an opportunity to enhance and transform it. AI cannot replace the human qualities that make lawyers valuable, such as critical thinking, good judgment, creativity and empathy. It may, however, be able to amplify those qualities and the focus now should be on understanding how users can achieve the best and most accurate results from AI. Lawyers who embrace AI as a tool to augment their skills and expertise will have a competitive edge over those who resist or ignore it.

This article was first published in Global Arbitration Review (October 2023).

Related expertise

Managing future disputes risks