A&O chips in with global tech savvy

Related people

Headlines in this article

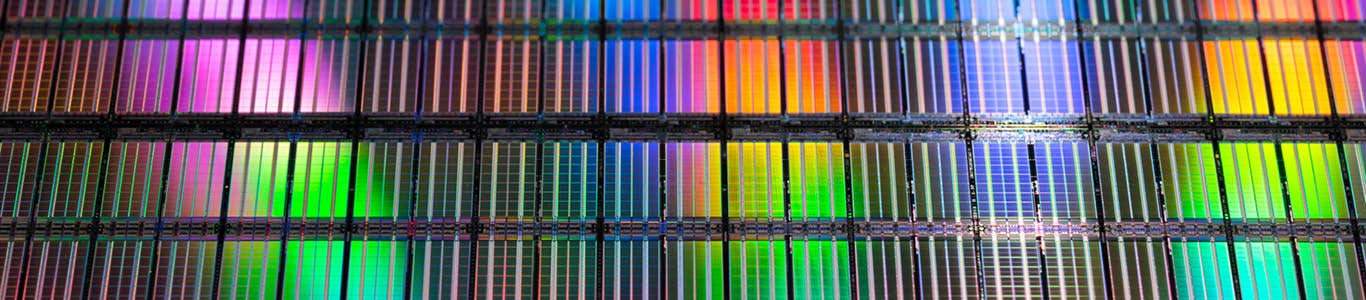

Have you tried to buy a car, a computer, a mobile phone or a household appliance in the last couple of years? Have you been told to expect long delays before your order is fulfilled?

There’s a high chance you have. It means you have probably fallen victim to a sudden shortfall in semiconductors, or microchips, as one of the world’s most powerful supply chains struggled to meet soaring demand for the chips that now drive so many aspects of life.

The Covid-19 pandemic was a root cause of the supply and demand crunch. Protracted lock-downs hit production at some of the biggest chip manufacturers, now mostly located in Asia. Disruptions also left ports choked, sending shipping costs soaring.

But it was mostly down to a sudden spike in demand for the office devices that enabled people to work effectively from home.

In addition, key industries misjudged the supply disruption and were caught on the hop.

Anticipating a sharp slowdown in demand for new vehicles as Covid-19 struck, some carmakers ran down their own inventories of semiconductors, which increasingly control important features such as braking, steering and navigation systems.

When demand returned – with a vengeance – carmakers were unable to secure ramped up production from their chip suppliers quickly enough to maintain delivery schedules, with an estimated eight million fewer cars built last year. They did not anticipate the need to lock in longer term supply, as other sectors stepped in front of the auto industry with their accelerating demand for chip capacity with other sectors of the economy (for example to power devices to make virtual work from home during the Covid-19 lock-downs).

Few sectors, however, were left unscathed, underscoring just how integral to life semiconductors have become. The wider economic impact was immense.

Analysts believe supply chain disruptions cost the U.S. economy an estimated USD240bn in lost GDP. Across the Eurozone the loss in GDP was put at EUR112.7bn, according to research published by Accenture at the 2022 World Economic Forum.

A renaissance

Supply chains began returning to normal in 2022 and just as quickly the industry was looking at an oversupply situation.

But, as Bijal Vakil, co-head of Allen & Overy’s Technology group, puts it: “We’re not out of the woods yet. We’re not back to business as usual and perhaps we never will be. Fresh outbreaks of the pandemic could cause issues again.”

The crisis has been a game-changer for the industry in so many ways, not least as chipmakers are now enjoying record revenues and profits on the back of rising demand.

In addition, venture capital investment in semiconductor growth companies soared to record levels in 2021, with USD9.9bn invested through 170 deals, according to Pitchbook.

Despite a slowdown in the first half of 2022, the industry is nevertheless in a new place.

As economies and industries digitalise, the demand for chips is rising everywhere: transportation, retail, healthcare, education, entertainment, government, public services, vital infrastructure and more. “The industry is experiencing a renaissance because it drives everything we do on a daily basis,” Bijal says.

Governments act on manufacturing

Given the strategic importance of semiconductors, the supply crisis has been a wake-up call for the industry and governments alike.

With many countries, including China, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, already investing billions in manufacturing capacity, the U.S. and the EU have been spurred into action.

In mid-2022, the U.S. Chips and Science Act was signed into law, unleashing some USD52bn of federal grants to catalyse the building of onshore manufacturing capacity with a focus on the smallest and most powerful chips.

It’s a significant intervention. While the U.S. still dominates the semiconductor market, its share of manufacturing capacity has plummeted, falling from 30% to 12% in the last 30 years, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association.

But Noah Brumfield, a competition law partner operating in our Washington, D.C. and Silicon Valley offices, puts the Act into context. “I think it’s a good step; but it’s a token step,” he says.

“It’s important that companies take advantage of these incentives to invest, but it’s a very small amount relative to the investment companies need to make in building new fabs, or manufacturing plants, which runs to tens of billions of dollars, and for continued research and development. The capital expenditure (capex) of Taiwan’s TSMC, the world’s biggest chipmaker, dwarfs what most companies are investing,” he says.

“In the U.S. we’ve let manufacturing drift offshore. Given the importance of semiconductors, that was a strategic mistake. That’s where the importance of this legislation lies, rather than in the actual dollar amount.”

And the impact has been immediate, with a number of players announcing plans to build new capacity. Intel has begun work on a USD20bn manufacturing facility in Ohio, and Micron Technology has announced plans to invest USD40bn by 2030 in producing high-end memory chips. Others, including inbound investors, are following suit.

The U.S. government is of course not alone in its investment efforts. The EU launched its own Chips Act in 2022, a framework unlocking EUR43bn of public and private investment, with the specific ambition of doubling Europe’s share of the semiconductor market from its present level of just under 10%.

Yvo de Vries, a partner in our Amsterdam office who brought his expertise in EU competition law and state aid regulation to the Technology group, says that could be a significant challenge. “The EU had a similar initiative launched in 2013 which failed,” he says. “The big question is: what are they going to prioritise?”

Europe, he explains, has never been strong in producing very small, high-end chips. Does it want to go head-to-head with the U.S., China and Taiwan to target this segment? “If that is what they want to do, EUR43bn is a very small amount.”

By comparison, government-backed investment funds tied to the Chinese semiconductor industry have an estimated 1 trillion in equivalent dollars available for spending over the next several years.

State aid, antitrust and national security challenges

To boost manufacturing capacity, the EU framework includes a significant relaxation of state aid rules for companies building first-of-a-kind facilities in the EU. Member states will have powers to issue fast-track permits.

Yvo fully expects to be advising clients on how to take advantage of both these measures, but also predicts that they could lead to legal conflict.

"I think we may very well see disputes, including complaints from competitors who feel that, wrongly, they have not been given preferential status. Other cross-border disputes are likely to emerge, not least as the EU is due to adopt the Foreign Subsidies Directive to tackle state aid granted by third countries.”

Antitrust law in both Europe and the U.S. is increasingly focusing on the semiconductor market, and, as in other areas of technology, regulators are clamping down on potential monopolisation of the market and national security.

That’s had a direct impact on M&A in the sector with several deals being blocked, including the proposed USD103bn acquisition of Qualcomm by Singapore-based Broadcom (blocked in 2018 on national security grounds) and U.S.-based NVIDIA’s USD39bn offer to buy the Cambridge semiconductor and software design company Arm, terminated in 2022 because of opposition from antitrust regulators.

Regulators are also “hyper-focused” on specific, narrow semiconductor applications, Noah points out. “Historically, there was a view that chips were chips, with a broader focus with only significant functional differences. But with advances in technology, there is a lot more attention to very narrow applications.

“Our clients need to give a lot more thought to how they present their cases, whether that’s in the context of a merger or in defending proposed ventures and agreements.”

The U.S. Chips Act prohibits any recipient of grants from investing in high-end chip manufacturing in China and other so-called “high-risk” jurisdictions, although investment in making lower-tech “legacy” chips will still be allowed.

We’re at the beginning stages of transforming and elevating the practice, bringing together all our capabilities and specialisms...

It’s a measure described by Noah as “belt and suspenders”, given that export controls already limit such investments. But it only underlines how technology in general, and semiconductors in particular, are being subjected to ever-tougher national security restrictions.

In the EU, Yvo is convinced similar provisions will be included in implementing regulations for the Chips Act.

IP litigation rising rapidly

The semiconductor industry is, in one sense, becoming a victim of its current success. We are seeing a sharp rise in IP and patent litigation, in particular suits brought by so-called non-performing entities (NPEs) – companies that exist to derive licence fees from their patents or, often, to seek settlements for alleged patent violations.

Bijal again: “We’re seeing a big rise in this activity because chip companies are flush with cash, and when you’re flush with cash you become a target. NPEs are trying to leverage the quite liberal damages framework in the U.S. to gain settlements.”

Jill Ge, an IP litigation partner in our Shanghai office, says it’s a new area of complexity for the tech sector that is not unique to the U.S. “NPE litigation has emerged in China,” she says.

Our ambitious technology plans

This kaleidoscope of issues affecting the semiconductor industry is a perfect example of why A&O has reconfigured its capabilities to create a powerful new Technology group.

Since early 2021, A&O has vastly expanded its global team, welcoming a team of eight partners from White & Case LLP together with important lateral hires in Washington, D.C. and New York and opening new offices in Palo Alto, San Francisco and Los Angeles. The premise is simple: with the world on a dizzying journey of digital transformation, every client is a tech client now.

“It’s a really exciting time for our Tech group,” says Bijal. “We’re at the beginning stages of transforming and elevating the practice, bringing together all our capabilities and specialisms, making it much more inter-disciplinary and focusing that effort.”

We look for the expertise beyond the practice.

The move is in line with A&O’s decision to build its growth ambitions around three strategic macroeconomic trends: private capital, sustainability and technology.

And it is a strategy built around clients, reflecting how they go to market, as Rose Hall, Global Head of Sector Business Development, based in London, explains.

“Clients want the best of both worlds. They want their lawyers to have deep technical expertise in all the relevant areas, but they also want them to have a good understanding of their business and the sector they operate in. By bringing our resources into this group, we are well on the road to meeting that demand,” she says.

The group’s organising principle is summed up in three words: create, navigate and protect. Create is about advising clients on how to bring their ideas to life in the form of new technologies, new companies or new business models. Navigate describes helping clients make their way through growing legal and regulatory complexity. Protect is about being at the side of our clients when they need to defend the tech they own.

The new West Coast offices place A&O right at the heart of what is still the world’s most important tech hub. But the firm also has superb capabilities in the world’s other tech centres of excellence: London for fintech, China for electric vehicles, Taiwan for semiconductors and Brussels for new regulatory issues.

“The secret is to get our lawyers to work in a truly collaborative way,” says Noah. “We look for the expertise beyond the practice.”

Jill Ge agrees. “Our approach aligns with the way clients do business. They don’t organise themselves around different issues, whether that’s IP litigation, export controls or antitrust regulation. They are focused on selling their products and getting ahead of their competitors.

“I think we are making a great job of breaking down the walls between practices.”

The group’s Tech Board brings together partners from across the network, and it has created 12 workstreams to enhance client focus. The workstreams include fintech and digital assets, digital health, hardware, platforms including software, and social media.

Bijal says it helps the team focus on what matters most to clients. “It’s not perfect because many clients fall into a number of these workstreams. But it’s an effort to take control and make sense of something as vast as the word technology.”

The ultimate ambition is for A&O to become as renowned in technology as it has always been in finance. Is that ambition one that the firm is being publicly explicit about?

“Absolutely,” says Bijal, without a pause.

Recommended content