- Home

- Blogs

- Compact Contract

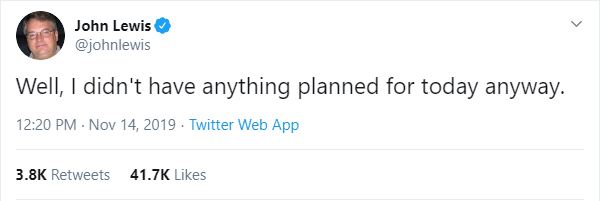

Nevermind the John Lewis ad, the latest update to Lewison is out

Blog Post

18 November 2019

Browse this blog post

Nevermind the John Lewis ad, the Christmas event for the true contract law geek is the supplement to The Interpretation of Contracts by Sir Kim Lewison. So here's a summary of some of what made it to latest update (just out, but the cut-off date for developments is 31 July 2019):

- Deleted words: unsurprisingly, Lewison sides with Singh LJ in Bou-Simon (who had agreed with the earlier edition of Lewison) that deleted words may negative the implication of a term in the form of the deleted words.

- Explanatory note: the court has relied on an ISDA user guide interpreting the ISDA standard form agreement even when the user guide post-dated the contract.

- Entire agreement clauses: were considered in a number of cases.

- Limitations on the use of background: for some documents—like the rules of a pension scheme—which are formal, are not the product of negotiation, are designed to operate in the long term and confer rights on third parties, the use of the background is limited.

- Standard form agreements: while courts at first instance will regard previous decisions of considerable value, an appeal court may feel less constrained.

- Headings: there have been a number of cases which have downplayed the relevance of headings to interpretation (which is comforting in the light of problematic obiter comments pointing the other way even when the agreement expressly stated the headings were to be ignored).

- Good faith: unsurprisingly the Bates v Post Office case gets a number of mentions including listing out the characteristics of a "relational contract" identified by the court.

- Implication of terms vs. interpretation: there's an explicit acknowledgment by Lewison, contrary to the main volume, that interpretation is a different process to implication and governed by different rules. The estate agent's case, Wells v Devani, which found that a short telephone call was enough to create a binding agreement between an estate agent and his client, even though the trigger event for the commission had not been specified, gets a number of mentions. This includes the obiter comments that there is no general rule that it is impossible to imply a term into an agreement to render it sufficiently certain to constitute a binding contract.

- Contra proferentem (against s/he who puts them forward): most of the commentary is about scepticism towards this maxim which, on one view, has only skeletal remains. Prof Burrows has a useful discussion of the rule here.

- Ejusdem generis (of the same kind): is seen as a flexible aid to construction.

- Saving the document: if the court is to prefer one interpretation to another in order to save a document, both proposed interpretations need to be realistic.

- Agreements to agree: Morris v Swanton Care gets a mention. This was where the Court of Appeal held that an earn-out provision in a share purchase agreement contained an unenforceable agreement to agree.

- Exclusion clauses: First Tower Trust gets a mention. This was where the Court of Appeal decided that clauses excluding mis-representation under the 1967 Act must be reasonable.

- Force majeure: has been an area of activity.

- Contractual discretion: a number of cases are mentioned including Equitas v Municipal where the Court of Appeal implied term in the context of reinsurance of mesothelioma claims.

- When is a term, a condition? Ark Shipping v Silverburn Shipping gets a mention. This is where the Court of Appeal had to deal with the law school classic: when is a term a condition, the breach of which entitles the innocent party to terminate, and when an innominate term, where the ability to terminate depends on the gravity of its breach?

- Penalties: Triple Point v PTT gets a mention. This is where the Court of Appeal considered to what extent liquidated damages continue to be payable when a project falls into delay and the contract is subsequently terminated or the contractor replaced.