Equalisation/GMP equalisation

30 years have passed since the landmark Barber judgment, but equalisation issues are still giving rise to pensions disputes, with a potentially large price tag attached. Following the Lloyds decisions, equalisation for the effect of guaranteed minimum pensions (GMP equalisation) is also a hot topic.

What is equalisation?

Pension schemes used to provide for different normal retirement ages for men and women, reflecting the different ages at which state pension benefits became payable. The difference is still reflected in aspects of scheme design, such as past periods of contracted-out service (guaranteed minimum pension (GMP) ages are 65 and 60, respectively, for men and women).

30 years ago, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) decided in Barber that the right to equal pay for men and women (at the time, contained in Article 119 of the EEC Treaty) applied to occupational pension schemes, and that it was in breach of this principle to provide for different age conditions for men and women. Mr Barber’s complaint related to the fact that on redundancy, he was only entitled to a deferred pension, whereas a woman of the same age would have been entitled to an immediate retirement pension.

The ECJ imposed a time restriction on the effect of the judgment, so that Article 119 could not be relied upon to claim entitlement to a pension calculated on an equalised basis for service prior to the decision (17 May 1990), with the exception of claims and legal actions that were pre-existing.

So, for any period of pensionable service prior to 17 May 1990, equalisation of pension ages was not required. For the period between 17 May 1990 and the date that the scheme rules were equalised (known as the ‘Barber window’), pension rights were ‘levelled up’, that is, the disadvantaged members were entitled to the more favourable treatment, which generally meant that male members were entitled to a lower retirement age.

Following the case (and subsequent cases which clarified the effect of Barber), schemes took steps to ‘equalise’ retirement ages between men and women by amending the scheme rules and issuing announcements to members. However, in many cases, the steps taken were insufficient to achieve equalisation – with significant consequences for scheme funding if the mistake was only discovered many years later.

Barber equalisation: if schemes took these steps many years ago, how and why are disputes still arising?

Barber equalisation issues can be identified in various ways – for example, as part of a due diligence exercise for a merger or acquisition, during a rules review, or following a change of scheme adviser. A contractual dispute could also arise between the trustees and an insurer in relation to a liability management exercise (such as a buy-in), or between corporate entities following a merger or acquisition. On occasion, individual members have also complained to the Pensions Ombudsman.

A failure to properly equalise benefits under a scheme’s rules will result in a significant increase in the scheme’s liabilities and will often result in a professional negligence claim against the advisers who failed to advise on the correct way to equalise or identify that the rules had not been validly amended. As time passes, bringing a professional negligence claim in relation to equalisation issues is likely to become increasingly complex because a claim may be out of time, or because of the difficulty of gathering sufficient evidence. To read more about professional negligence claims, visit www.allenovery.com/profneg.

Court claims in relation to equalisation arise mainly in four ways:

- the parties cannot agree on whether equalisation has been achieved and either seek clarification from the court or ask the court to agree a settlement of the disagreement;

- the parties agree on the position but seek the court’s confirmation as to the correct position;

- the parties seek to rectify the document that failed to give effect to equalisation; or

- the failure to equalise is not in doubt but the trustee/employer brings a professional negligence claim against the scheme’s advisers.

To read more about High Court claims, visit www.allenovery.com/highcourt.

Going to court on an equalisation dispute is not necessarily a bad thing, although the risks and benefits need to be assessed in each particular case. Where there is uncertainty or disagreement, a court decision that equalisation was properly effected on a particular date would have the effect of reducing the liabilities that an employer would otherwise face, but an unfavourable decision by the court would have the opposite effect (and the parties would also incur the additional cost of litigating the dispute). The key point, however, is that trustees need to pay the correct benefits and therefore need to know how to calculate those benefits so that they are compliant with the equal pay requirement.

Recent cases

Some recent cases involving Barber equalisation issues include:

- Member notice effective to achieve equalisation

- Deed of intention on equalisation effective to amend scheme

- Amendment power formalities not met

- Complaint about retrospective change to equalisation date not upheld

- Rectification granted for equalisation error

- Faulty equalisation amendment cured by interpretation

Member notice effective to achieve equalisation

In Vaitkus v Dresser-Rand (2014), the High Court held that a notice issued in 1991 to female members was effective to equalise the scheme’s normal retirement date at age 65 for men and women, despite a conflicting provision in a subsequently executed definitive deed and rules.

Deed of intention on equalisation effective to amend scheme

In Premier Foods v RHM Pension Trust (2012), the High Court held that a 1990 deed declaring an intention to equalise normal retirement ages between men and women, and stating that the scheme should be operated as if the changes had already been made, was effective to achieve equalisation. If this argument had not succeeded, and the scheme had been equalised several years later when a deed of amendment was executed, the cost to the scheme sponsor would have been just under GBP18 million.

Amendment power formalities not met

In Safeway v Newton (2017), the Court of Appeal considered whether normal pension ages (NPA) had been equalised at age 65 in 1991, by a member announcement. The Court of Appeal ruled the announcement was ineffective to change the NPA, as the rules required amendments to be made by deed (this was not done until 1996). The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) was then asked if retrospectively amending the rules to equalise NPA was prohibited under European law.

The CJEU ruled that retrospectively ‘levelling down’ retirement ages to the less favourable treatment is prohibited, unless there is objective justification. In a subsequent decision (2020), the Court of Appeal unanimously ruled that section 62 of the Pensions Act 1995 closed the Barber window with effect from 1 January 1996. Section 62 contained a statutory equal treatment rule, and has since been replaced by the Equality Act (to read more about the Equality Act and pensions, visit www.allenovery.com/discrimination). The Court of Appeal did not consider the objective justification issue, as this argument was not pursued.

This decision will be of interest to schemes that sought to retrospectively equalise retirement ages between 1 January 1996 and 6 April 1997 (when section 67 of the Pensions Act 1995 came into force, preventing certain retrospective amendments).

To read more about the importance of meeting formalities requirements, visit www.allenovery.com/amendments.

Complaint about retrospective change to equalisation date not upheld

In Mr S (2016), a member complained to the Pensions Ombudsman about a retrospective change to the scheme equalisation date, which reduced his pension. Mr S retired in 2005; in 2009, the trustees reviewed the equalisation date, took legal advice and amended the equalisation date (to the date the trustees said was originally intended). In dismissing the complaint, the Deputy Pensions Ombudsman stated that she had no authority to decide the correct date for equalisation as this would affect a number of other scheme members, and would only decide whether the trustees had erred in law or had committed maladministration by deciding to administer the scheme as equalised on the earlier 1992 date.

Rectification granted for equalisation error

In Industrial Acoustics v Crowhurst (2012), the High Court granted rectification for errors in normal retirement dates for men and women. The rules had been amended by resolution in 1992 and 1995 to equalise benefits between men and women. A new set of rules from 1998 (which had been prepared in 1992 but had not been updated to reflect the 1995 change) and a 1999 resolution essentially reversed the effect of the 1995 resolution. The judge was satisfied that the employer and trustee had always intended the 1995 resolution to have effect and granted rectification. To read more about these types of claims, visit www.allenovery.com/rectification.

Faulty equalisation amendment cured by interpretation

In ICM v Stribley (2013), an employer sought a declaration from the High Court about the meaning of a 1997 equalisation amendment. The amendment dealt with NPA up to the amendment date, but did not expressly state the subsequent NPA. The judge ruled that the rules should be read as including the missing provision, as it would have been obvious to the reasonable reader that an omission had been made. This was treated as an issue of interpreting the rules, rather than rectifying a mistake. To read more about these issues, visit www.allenovery.com/interpretation and www.allenovery.com/rectification.

What is GMP equalisation?

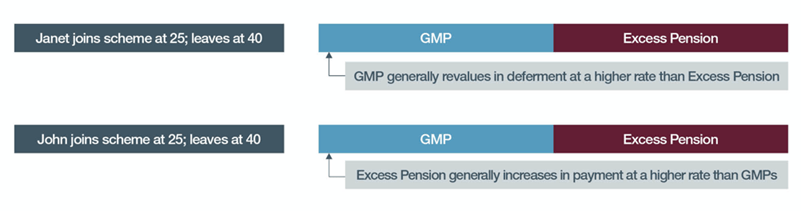

Schemes that were ‘contracted-out’ are required to provide GMPs (specific statutory requirements apply). Inequalities in total pension may arise for reasons including the different ages at which the GMP comes into payment for men and women, and rates of revaluation and indexation:

After many years of uncertainty, the High Court ruled in October 2018 that benefits should be equalised for the effect of unequal GMPs – the judge considered several proposed methods for equalisation (see our briefing for details). One potential method involves using the statutory framework for GMP conversion – the government has published guidance on using this method, but there are a number of unresolved issues - read more. HMRC has also issued guidance on various tax issues arising from corrective payments.

A further ruling, in 2020, considers issues around correcting past transfers out . We act for the trustee in this case. This is a complex area and both trustees and sponsors should seek legal and other professional advice on the implications for their scheme.

A further issue that should be considered at an early stage is the payment of arrears, as the judge considered that a scheme’s forfeiture rule could operate to limit this. Trustees should take advice on their rules and decide an appropriate approach for their scheme.