State of play: a review of sovereign immunity cases

Related people

Headlines in this article

Related news and insights

Publications: 03 April 2024

Blog Post: 28 March 2024

News: 27 March 2024

News: 26 March 2024

A&O advises CVC on the financing of its investment in Monbake

Over the last five years there have been more than 50 hearings before the English courts concerning states and their immunities and, the most recent, the Heiser case, despite being a tragic and extreme example, is illustrative of the issues that they raise: they are geo-political in origin, the litigation is long running and multijurisdictional and procedural matters, specifically whether service is valid, are important.

I have taken a look at these 50 or so decisions to see what patterns emerge. For a sizeable chunk (18.5%), the original proceedings were arbitration. States tend to prefer arbitration to litigation because it is private and, provided there is no court supervision, it need not infringe a state's immunity.

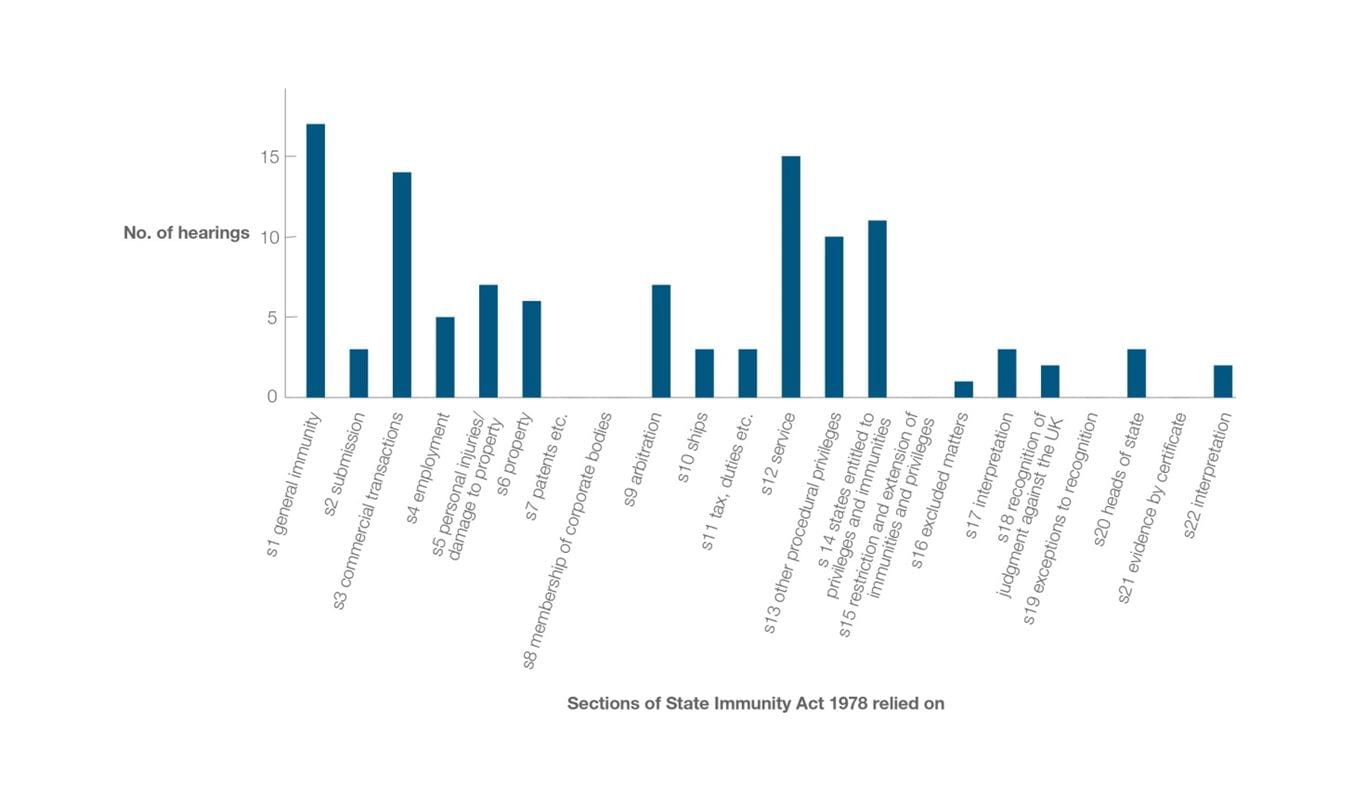

As in the Heiser case, service is an issue in over a quarter (27.8%) of the cases reviewed. It is a frequent stumbling block for the non-state party. This stems from section 12 of the State Immunity Act 1978 which says "Any writ or other document required to be served for instituting proceedings against a State shall be served by being transmitted through the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the State". This provision has been raised in 14 hearings over the period surveyed. Recently, in General Dynamics v Libya, the Court of Appeal held that it was not mandatory for either an arbitration claim form or an order permitting the enforcement of an award as a judgment to be served through the FCO, neither being a "writ or other document required to be served for instituting proceedings". At the same time the court made it clear, obiter, that where such an instituting document is involved the court has no power to dispense with service.

Related expertise

Another area of activity is around section 13 and the so-called "other procedural privileges". Most often this concerns enforcement of a judgment or award and other related steps such as attachment to property. This is probably one of the biggest challenges for those ending up in disputes with states: actually getting hold of the money if they are successful. Understandably, states vigorously defend immunity and especially in this context. In the absence of express consent by the state to these measures – the granting of orders for the recovery of property, the attachment of its assets, and its property being subject to any process for the enforcement of a judgment or arbitration award – the non-state party will face an uphill struggle when it comes to execution.

The significant percentage of claims that originate in arbitration make it unsurprising that section 9 of the Act was raised in seven of the hearings reviewed. By this provision, a state's agreement to arbitration means that the state is not immune from proceedings in support of that arbitration. This makes dispute resolution by arbitration attractive to non-state parties. However express consent to the "other procedural privileges" listed in section 13 is still required.

Who is entitled to immunity, chiefly whether the party to a dispute is a state or "separate entity" distinct from the executive organs of government, is a fact dependent issue. It is in part for this reason that section 14 – which sets out when a separate entity is entitled to immunity – was raised in 13 hearings.

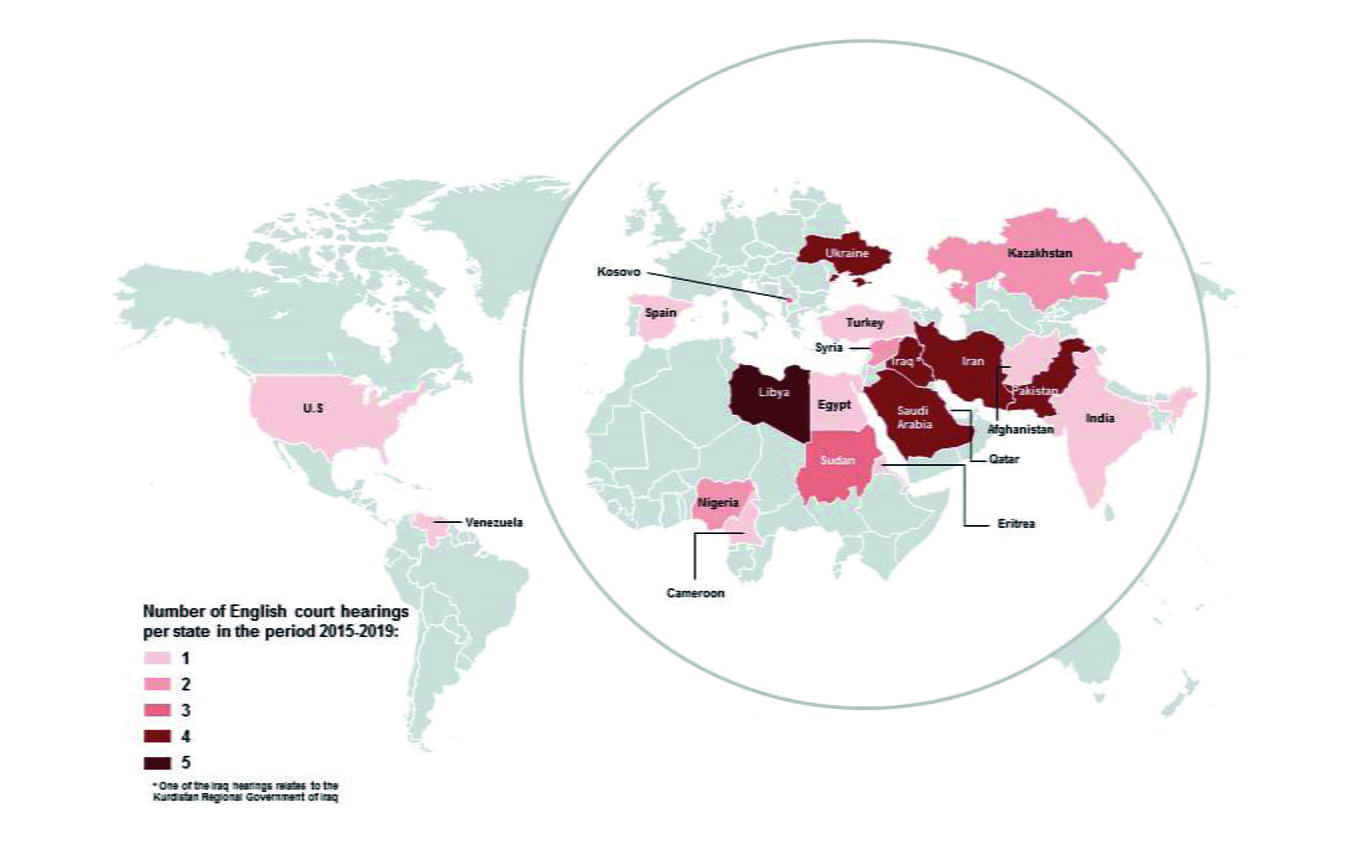

The states that are party to litigation are often, but by no means exclusively, those associated with conflict: a number of hearings concerned Libya, Iraq, Ukraine, Kosovo and Syria. The disputes being litigated can still be commercial: Russia seeking payment from Ukraine under matured Eurobonds (Ukraine v Law Debenture) and the EU seeking repayment from Syria under a series of commercial loans (EU and EIB v Syria) in which Allen & Overy acted.

Litigation involving states is hard fought and often raises complex legal questions such as when the foreign act of state doctrine applies (Belhaj v Straw), how to analyse the capacity of a state (Ukraine v Law Debenture) and the interaction between EU law and national law (Benkharbouche). This can be seen by the fact that there have been five Supreme Court decisions in the last five years and eight Court of Appeal hearings.

Next June, the Court of Appeal is scheduled to this tally by hearing Mohamed v Breish. It will consider the so-called "one voice" doctrine. This holds that where the FCO chose to recognise someone has having the executive authority of a foreign state (here, Libya) the court should not look behind that recognition. Around the same time, I intend to publish an update to this piece and I am expecting more challenges to service and potentially an appeal to the Supreme Court of the General Dynamics v Libya case.